Simply Satisfaction: Cobots do everything (but what you want to do), critically questions what extent a human needs to be involved in a task, and what can be automated so it can be optimally satisfying for the user. As artificial intelligence and robotics becomes more ingrained in everyday life, rather than purely focus on efficiency as a form of output or a value system, and replacing humans who have a natural desire to create, we need to focus on designing humans into the role of automation. The devices of Simply Satisfaction explore this division of labor through futuristic home devices that collaboratively automate the functionality of their task. The ideal experience, is not that the task is fully automated, but instead it has varying levels, or parts, that are automated. Some explore the satisfaction of collaboration by building the device, some training the device, and others train you. These devices augment the user in tasks everyone understands and relates to, while focusing on how the devices make the job simply more satisfying.

Key takeaway:

Overall this piece was extremely successful, and I learned a lot from it. I think it took a big step forward in exploring what user experience for artificial intelligence and collaborative robots is. In the future of AI, allowing users to be able to custom train their algorithm to best work collaboratively will develop better human centered user experience, but at the same time will start to build the foundation of how we create a better experience for the algorithm itself.

As this technology evolves, we need to start being concerned, not so much on we push the boundaries of AI, but really start to think about how it is designed. What are the ethical implications of training and building an algorithm. I think user experience design for AI is an important factor in this innovation processes. User experience for AI will not be a one to one replica of what it is for human centered design, it can’t be. It might be more similar from a qualitative standpoint, and it will definitely be different from a quantitative standpoint, but it’s very much needed. Through this piece I believe user experience for AI is reflexive to human centered user experience. In order for it to be designed and developed, it has to be built keeping in mind the needs and interactions of the users it will be collaborating with. Ultimately the algorithm will be working with humans at its output.

One and half year thesis project.

Specifitaction:Design research, UX design, physical computing, speculative design, UX for AI

Execution: Prototyping, AI/machine vission, Raspberry Pi, 3d printing, sewing

Exploration: Simply Satisfaction: Cobots do everything (but what you want to do), critically questions what extent a human needs to be involved in a task, and what can be automated so it can be optimally satisfying for the user.

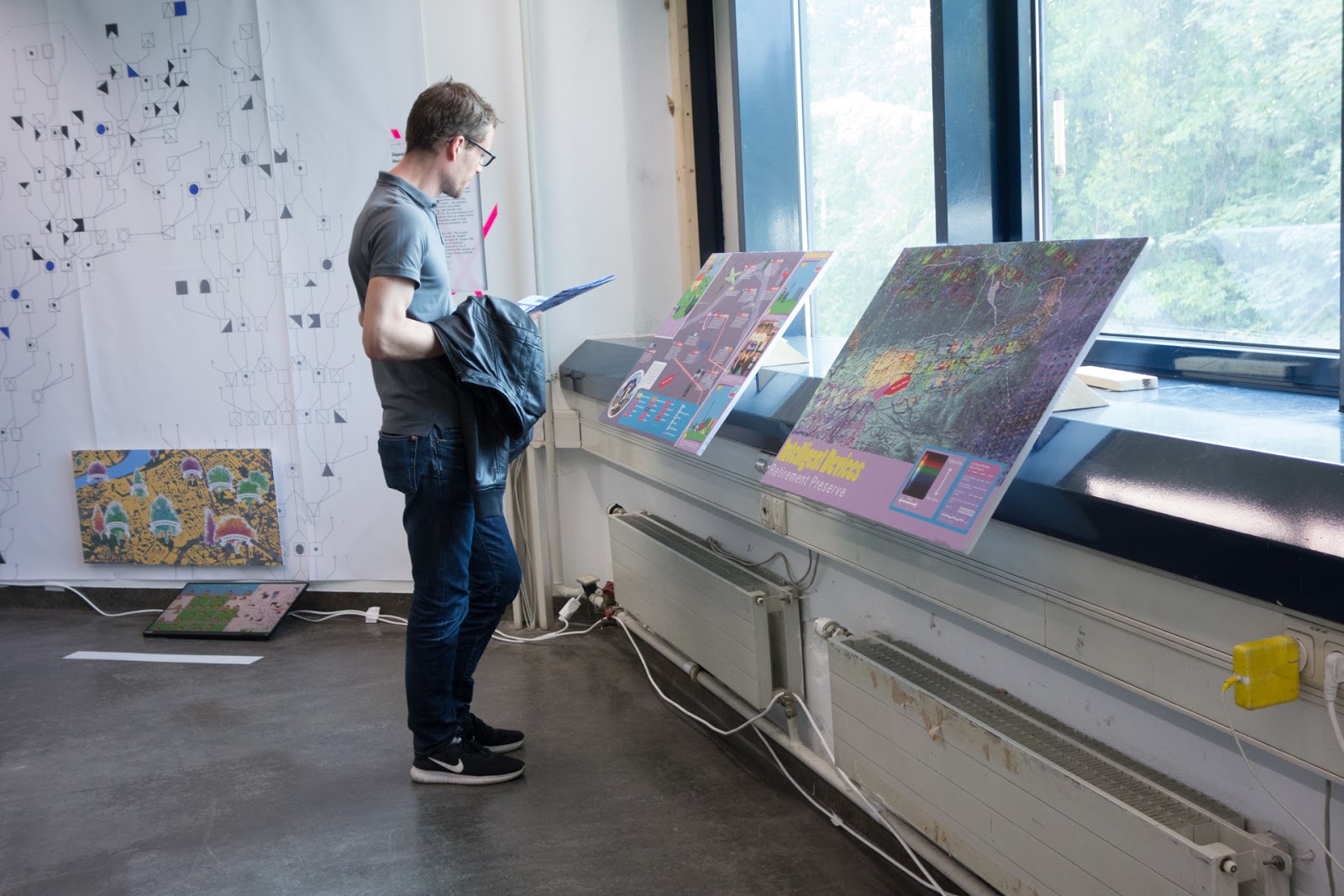

Part 1: Gallery show

Part 2: Cobots and their people

Part 3: Case Study

Things in bold are key points

Images from the Media Design Practices Graduate Show

![]()

These are the videos from the gallery installation showing the experiments with each device and a little bit about them.

Gleb collaborating with the Laundry Folding cobot: Laundry Folding cobot trains Gleb on the best way to place his clothing on the device so it can fold it to his folding preferences.

Gleb collaborating with Laundry De-Sorter cobot to launch and spread his clean laundery by density, so its more satisfying for him to fold things. Sometimes you want to automate a specific part of the process... just becuase you find it satasifying.

Barb mutually collaborating with Scissor cobot to cut paper. Scissor cobot reposistions the user by allowing them to experience the satisfaction of the cutting sensation, but making it so they have to work with the device to carry the task out.

Sarah collaborating with Laundry Roller cobot. Laundry Roller cobot isnt really great at its task, but it has really quirky cobotalities (much like human personalities but for cobots) that make it satisfying to work with from time to time.

Mike (me!) training Laundry Soap Dispencing cobot on how to poor laundry detergent into the washer.

This is an early exploration of what collaborating with artificially intelligent automation through the laundry process would be like.

This is an experiment using role playing to better understand what collaborating would be like throughout the whole laundry experience. The experiment focuses on what it would be like for the human to be able to step in at any point of the process to do the part that they enjoy doing, while automating everything else.

Simply Satisfaction Case Study

This project started from further exploring an earlier piece that I had done called Intermediary Transcendence Proxy (ITP)(2016)(see right). Each scenario of ITP explores a technical device’s functionality while putting the power and labor back in the hands of the worker. The project was an important foundation of Simply Satisfaction because it explored the relationship between future speculative devices that served both as a proxy and extension of workers collaborating with them.

ITP is an exploration of the future of labor that challenges and pushes the limits of Marshall McLuhan's concepts of media. Specifically the quote:

“All media are extensions of some human faculty – psychic or physical”

To read more about ITP and a critical analysis of the piece please click on the link below.

https://michaelmilanodesign.cargo.site/Intermediary-Transcendence-Proxy

As I started this piece, and similarly with ITP, I was very interested in how algorithms, the devices that they embody, and the workers that work with them are all separate employees/coworkers. In ITP this isn't fully the case, because the devices are a means for other workers to work in a remote area. But the tongue-in-cheek animation starts to explore this new form of collaboration and the outcomes of not completely automating everything that can be automated.

The references and inspirations of ITP were also very much influential in the early stages of the piece as well. References like Kelly Dobson’s piece Omo or Mark Shepards’ piece Sentient City Survival Kit impacted the types of interactions and user experiences I wanted to explore in these new divisions of labor. This was something that I had started to think about while writing a critical analysis of ITP as explained in the excerpt below.

“Most of the more absurd examples Disalvo references (like Omo, see below), are odd/surreal, but that oddity is a tool to reinforce an interaction between the user and the design that situates the user in agonism. This further allows them, through an interaction of some kind, to develop a greater understanding and to form their own opinion on the subject matter. I think in future iterations of this piece it would be interesting to make something tangible, whether that be a piece of software or physical space that allows for the user to further experience this series of dynamics. Actually making the interactive proxies, with corresponding software, to immerse the user into this proposed future would be an interesting next step, and would provide the platform needed to further discuss the issues at hand and create a stronger sense of agonism.”

This project started from further exploring an earlier piece that I had done called Intermediary Transcendence Proxy (ITP)(2016)(see right). Each scenario of ITP explores a technical device’s functionality while putting the power and labor back in the hands of the worker. The project was an important foundation of Simply Satisfaction because it explored the relationship between future speculative devices that served both as a proxy and extension of workers collaborating with them.

ITP is an exploration of the future of labor that challenges and pushes the limits of Marshall McLuhan's concepts of media. Specifically the quote:

“All media are extensions of some human faculty – psychic or physical”

To read more about ITP and a critical analysis of the piece please click on the link below.

https://michaelmilanodesign.cargo.site/Intermediary-Transcendence-Proxy

As I started this piece, and similarly with ITP, I was very interested in how algorithms, the devices that they embody, and the workers that work with them are all separate employees/coworkers. In ITP this isn't fully the case, because the devices are a means for other workers to work in a remote area. But the tongue-in-cheek animation starts to explore this new form of collaboration and the outcomes of not completely automating everything that can be automated.

The references and inspirations of ITP were also very much influential in the early stages of the piece as well. References like Kelly Dobson’s piece Omo or Mark Shepards’ piece Sentient City Survival Kit impacted the types of interactions and user experiences I wanted to explore in these new divisions of labor. This was something that I had started to think about while writing a critical analysis of ITP as explained in the excerpt below.

“Most of the more absurd examples Disalvo references (like Omo, see below), are odd/surreal, but that oddity is a tool to reinforce an interaction between the user and the design that situates the user in agonism. This further allows them, through an interaction of some kind, to develop a greater understanding and to form their own opinion on the subject matter. I think in future iterations of this piece it would be interesting to make something tangible, whether that be a piece of software or physical space that allows for the user to further experience this series of dynamics. Actually making the interactive proxies, with corresponding software, to immerse the user into this proposed future would be an interesting next step, and would provide the platform needed to further discuss the issues at hand and create a stronger sense of agonism.”

Main Points/takeaways

This project started from further exploring an earlier piece that I had done called Intermediary Transcendence Proxy (ITP) which explores a technical device’s functionality while putting the power and labor back in the hands of the worker.(see below)

I was very interested in how algorithms, the devices that they embody, and the workers that work with them are all separate employees/coworkers.

This project started from further exploring an earlier piece that I had done called Intermediary Transcendence Proxy (ITP) which explores a technical device’s functionality while putting the power and labor back in the hands of the worker.(see below)

I was very interested in how algorithms, the devices that they embody, and the workers that work with them are all separate employees/coworkers.

In both references, especially Omo, I really liked how the devices started to create a more lifelike entity that became more than just a tool. These collaborators, being nonhuman, started to make me think about what it would be like if artificially intelligent devices were to develop a non-human personality.

I really liked how the devices, like Omo by Kelly Dobson, started to create a more lifelike entity that became more than just a tool. These collaborators, being nonhuman, started to make me think about what it would be like if artificially intelligent devices were to develop a non-human personality.

This led to another piece Intelligent Devices Retirement Preserve, which further began to develop the foundation of Simply Satisfaction. Intelligent Devices Retirement Preserve imagines a parkland where intelligent agricultural machinery can continue to roam and interact with people after decommissioning. The piece considers roles for specific classes of smart devices beyond the end of their designed obsolescence, particularly autonomous farming equipment; which will have acquired a unique data set of pastoral media through a life of tending crops and livestock. Intelligent Devices Retirement Preserve was apart of the show The Internet of Enl!ghtened Things at Ars Electronica 2017: AI/ The Other I in Linz, Austria. (Piece at Ars Electronica below + right)

https://ars.electronica.art/ai/en/internet-of-enlightened-things/

https://ars.electronica.art/ai/en/internet-of-enlightened-things/

ITP led to Intelligent Devices Retirement Preserve imagines a parkland where intelligent agricultural machinery can continue to roam and interact with people after decommissioning, which was apart of the show The Internet of Enl!ghtened Things at Ars Electronica 2017: AI/ The Other I in Linz, Austria.

With this piece, I was still exploring how to define this relationship that humans have with future intelligent devices. I found it important to put the viewer in a position of having to question how they felt about giving a robot or device a retirement. A lot of the references and research for this piece revolved around companies that have implemented robotic automation but expected the human workforce that they kept on the job to keep up with the output of the machines. Having human viewers know that workers are being held to this expectation of output helped position them to question how we treat robots and if our expectation of automation is to much.

This piece simply aimed at challenging the viewer to see if they would be ok with an intelligent device having downtime, a retirement of some sort, or even the choice to keep working. This was a crucial point that evolved in Simply Satisfaction, because the concept/question later evolved into whether a human would be willing to work with an intelligent device as a colleague, and more importantly whether a human would be willing to implement automation for the sake of making a worker's job and life more satisfying.

This piece simply aimed at challenging the viewer to see if they would be ok with an intelligent device having downtime, a retirement of some sort, or even the choice to keep working. This was a crucial point that evolved in Simply Satisfaction, because the concept/question later evolved into whether a human would be willing to work with an intelligent device as a colleague, and more importantly whether a human would be willing to implement automation for the sake of making a worker's job and life more satisfying.

With this piece, I was still exploring how to define this relationship that humans have with future intelligent devices. I found it important to put the viewer in a position of having to question how they felt about giving a robot or device a retirement.(Piece at Ars Electronica below)

![]()

I later reflected and wrote a paper on the piece and it was published by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence under the UX for AI category in 2018. The paper discussed the ethical implications of giving the choice of retirement to an intelligent device or making it work until it’s death. Furthermore, by making the viewer/reader explore this concept it underscored the need for user experience design for artificial intelligence.

https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/SSS/SSS18/paper/view/17522

Both of these pieces still only speculated about the idea of having working colleagues that were algorithm or robotic-based, or what user experience design would be for these technological entities, but they never put any of the concepts into practice. Building off these pieces I began to work on the early stages of Simply Satisfaction.

https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/SSS/SSS18/paper/view/17522

Both of these pieces still only speculated about the idea of having working colleagues that were algorithm or robotic-based, or what user experience design would be for these technological entities, but they never put any of the concepts into practice. Building off these pieces I began to work on the early stages of Simply Satisfaction.

I later reflected and wrote a paper on the piece and it was published by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence under the UX for AI category in 2018. The paper discussed the ethical implications of giving the choice of retirement to an intelligent device or making it work until it’s death. Furthermore, by making the viewer/reader explore this concept it underscored the need for user experience design for artificial intelligence.

At this point, I was quite eager to start making and experimenting with what human interactions would be like with collaborative devices. I was still working on defining what collaboration really meant, but I knew ultimately that the piece had to have functioning machine learning or artificial intelligence, that/those algorithms had to be embodied in a device, and there had to be an exchange between the user and the other two “coworkers”.

As I began working on this piece, I started by exploring with low-fi wood mockups and role-playing. The first piece I made was a wooden model of a robotic arm and had two friends roleplay as the robotic arm and the worker. They had the task of trying to move blocks from a cart to a table. The goal was to use a set of rules/ restrictions to force the two to work together and find out what kind of outcomes would happen.

It also occurred to me that I kept thinking about and exploring automation inside of factories and around labor, but had never really been to a factory or talked to anyone that worked in an environment that housed automation. With that realization, I scheduled two interviews/ field trips. The first was to everyone's favorite hot sauce maker Huy Fong Foods Inc. the makers of Sriracha, and the second was Lagunitas Brewing company.

As I began working on this piece, I started by exploring with low-fi wood mockups and role-playing. The first piece I made was a wooden model of a robotic arm and had two friends roleplay as the robotic arm and the worker. They had the task of trying to move blocks from a cart to a table. The goal was to use a set of rules/ restrictions to force the two to work together and find out what kind of outcomes would happen.

It also occurred to me that I kept thinking about and exploring automation inside of factories and around labor, but had never really been to a factory or talked to anyone that worked in an environment that housed automation. With that realization, I scheduled two interviews/ field trips. The first was to everyone's favorite hot sauce maker Huy Fong Foods Inc. the makers of Sriracha, and the second was Lagunitas Brewing company.

I was still working on defining what collaboration really meant, but I knew ultimately that the piece had to have functioning machine learning or artificial intelligence, that/those algorithms had to be embodied in a device, and there had to be an exchange between the user and the other two “coworkers”.

The first piece I made was a wooden model of a robotic arm and had two friends roleplay as the robotic arm and the worker. They had the task of trying to move blocks from a cart to a table. The goal was to use a set of rules/ restrictions to force the two to work together and find out what kind of outcomes would happen.

I scheduled two interviews/ field trips. The first was to everyone's favorite hot sauce maker Huy Fong Foods Inc. the makers of Sriracha, and the second was Lagunitas Brewing company.

The first piece I made was a wooden model of a robotic arm and had two friends roleplay as the robotic arm and the worker. They had the task of trying to move blocks from a cart to a table. The goal was to use a set of rules/ restrictions to force the two to work together and find out what kind of outcomes would happen.

I scheduled two interviews/ field trips. The first was to everyone's favorite hot sauce maker Huy Fong Foods Inc. the makers of Sriracha, and the second was Lagunitas Brewing company.

While waiting on my interviews, I carried out the interaction experiments mentioned earlier. The rules were as follows, the person acting as the robot used the robot arm without stepping out of the green square (see right). The robot arm could be pivoted and craned however they wanted, but in order to open the clamping mechanism they had to pivot the arm in a way that tension from the clamps cable opened them. The human worker was allowed to assist the robot in moving the blocks but was to refrain as much as possible.

This experiment was successful in many ways but also failed in many ways. Automation always has restriction of some kind, but making the opening mechanism only work in from the pull cable was a bit too much restriction. Having a human roleplay a robot only works so much, because as the roleplaying progressed both people started to gamify the task at hand (which possibly could happen with future AI). This lends some insights into how we could make work more fun, but it doesn’t provide insights on how automation and collaboration could make work more satisfying.

It was a success because the human felt comfortable to step in and work with the robot. I know it’s not a real robot, which could be much more dangerous, but it still was a functioning mechanism and had some inherent dangers for the human to interact with it. The user's comfortability with working with the robot and the aspect of gamifying the experiment did reveal that human workers would enjoy having some form of a robotic coworker. From these insights, I began to plan the next stage of experiments. Additionally I was able to focus my questions for the tours more and overall had a better idea of what I wanted to get out of my visits.

This experiment was successful in many ways but also failed in many ways. Automation always has restriction of some kind, but making the opening mechanism only work in from the pull cable was a bit too much restriction. Having a human roleplay a robot only works so much, because as the roleplaying progressed both people started to gamify the task at hand (which possibly could happen with future AI). This lends some insights into how we could make work more fun, but it doesn’t provide insights on how automation and collaboration could make work more satisfying.

It was a success because the human felt comfortable to step in and work with the robot. I know it’s not a real robot, which could be much more dangerous, but it still was a functioning mechanism and had some inherent dangers for the human to interact with it. The user's comfortability with working with the robot and the aspect of gamifying the experiment did reveal that human workers would enjoy having some form of a robotic coworker. From these insights, I began to plan the next stage of experiments. Additionally I was able to focus my questions for the tours more and overall had a better idea of what I wanted to get out of my visits.

Having a human roleplay a robot only works so much, because as the roleplaying progressed both people started to gamify the task at hand (which possibly could happen with future AI). This lends some insights into how we could make work more fun, but it doesn’t provide insights on how automation and collaboration could make work more satisfying.

The first of the tours was with Huy Fong Foods Inc. The makers of Sriracha began offering tours of their facility to better educate the public of what and how they make their products. Their tour starts with a tram ride into the facility where they start to tell you all about the company's history. As you travel into the facility you can see walls of old or spare parts. Huy Fong Foods Inc. makes, repairs, and fabricates everything they use and sell at their facility in Irwindale, CA. This includes every bottle and bottle top that you buy in the store, and more importantly, they recycle everything on site as well. Once we entered the facility we were able to start to explore a bit and more importantly I was able to start to ask the staff questions. One of the interesting things I learned from the interviews, was that as the company grew they began producing everything on site, which allowed them to employ more people. After they moved from the Rosemead, CA location to their current location they implemented eight robotic arms. The surprising part of this addition was that when doing so they actually chose to increase the number of workers so they could employ people to do quality control for the jobs that the robotic arms and other automation were in charge of. These employees main responsibilities were to watch over their robotic coworkers and stop them if they began to make errors. This was an example of how it is possible to employ workers and have them work with automation rather than simply replace them.

My next interview was with Lagunitas Brewing, and it didn’t go as planned. First, I want to talk about why I wanted to talk to the people at Lagunitas. Lagunitas is a pioneer in water conservation for brewing. The average gallon of beer takes more then four gallons of water to produce. Lagunitas through innovation and engineering was able to get that number down drastically, which is why I wanted to see how the rather large midsize brewery was operating their soon to be open Azusa, CA location. As I mentioned this visit did not go as planned. It turns out the brewery is not open and doesn't exist. When I went to visit, the main facility was actually being rented out by Amazon fulfillment. However, they did plan on fabricating and building the facility by hand at the location, which was similar to Huy Fong Foods Inc.'s approach.

My next interview was with Lagunitas Brewing, and it didn’t go as planned. First, I want to talk about why I wanted to talk to the people at Lagunitas. Lagunitas is a pioneer in water conservation for brewing. The average gallon of beer takes more then four gallons of water to produce. Lagunitas through innovation and engineering was able to get that number down drastically, which is why I wanted to see how the rather large midsize brewery was operating their soon to be open Azusa, CA location. As I mentioned this visit did not go as planned. It turns out the brewery is not open and doesn't exist. When I went to visit, the main facility was actually being rented out by Amazon fulfillment. However, they did plan on fabricating and building the facility by hand at the location, which was similar to Huy Fong Foods Inc.'s approach.

After Huy Fong Foods Inc. moved from the Rosemead, CA location to their current location they implemented eight robotic arms. They actually chose to increase the number of workers so they could employ people to do quality control for the jobs that the robotic arms and other automation were in charge of. This was an example of how it is possible to employ workers and have them work with automation rather than simply replace them.

Based on my new insights, and from a few critiques, I started to explore the idea of disposable robots, and more specifically the implications of one use robots. I began with another low-fi experiment with the cellphone checking bot, which would allow the user to check their phone unnoticed once, and then be unusable. It was intended to be used in meetings or other events where you wouldn't want to get caught checking your phone. I began by Wizard of Oz’ing a situation using Raspberry Pi to actuate a servo that would hit the home button of the users phone. I was very interested in the tipping point or time when a person would use a one-use robot. I would start sending text messages to the phone until the user felt the need to use the bot. (seen right).

Based on my new insights, I started to explore the idea of disposable robots, with another low-fi experiment with the cellphone checking bot, which would allow the user to check their phone unnoticed once, and then be unusable. (below)

Ultimately after conducting the experiment I realized that it failed to capture a mutual working interaction between user and robot or algorithm. It did, however, allow me to start to explore the capabilities of working with a Raspberry Pi and robotics. It also revealed that I needed to get more specific with my experiments.

At this point, I began to work on exploring the idea of disposable intelligent robots through a speculative writing piece which became the topic of my thesis paper. I later presented a version of the paper at Smartness? Between discourse and practice hosted and led by the Architectural Humanities Research Association (2018 at TU Eindhoven). The paper Called Botco: Robots that can be thrown away consisted of two parts, a research paper and a speculative infomercial selling disposable robots.

At this point, I began to work on exploring the idea of disposable intelligent robots through a speculative writing piece which became the topic of my thesis paper. I later presented a version of the paper at Smartness? Between discourse and practice hosted and led by the Architectural Humanities Research Association (2018 at TU Eindhoven). The paper Called Botco: Robots that can be thrown away consisted of two parts, a research paper and a speculative infomercial selling disposable robots.

I realized that it failed to capture a mutual working interaction between user and robot or algorithm. It did, however, allow me to start to explore the capabilities of working with a Raspberry Pi and robotics. It also revealed that I needed to get more specific with my experiments.

I began to work on exploring the idea of disposable intelligent robots through a speculative writing piece called Botco: Robots that can be thrown away, which was presented at Smartness? Between discourse and practice hosted and led by the Architectural Humanities Research Association (2018 at TU Eindhoven).

I began to work on exploring the idea of disposable intelligent robots through a speculative writing piece called Botco: Robots that can be thrown away, which was presented at Smartness? Between discourse and practice hosted and led by the Architectural Humanities Research Association (2018 at TU Eindhoven).

While writing, I began exploring machine vision, which I could run and execute subscripts on a Raspberry Pi. After a bit of a rough installation process, I successfully was able to install Open CV on a Raspberry Pi and have the algorithm recognize faces. Once a face was recognized it would launch a separate python script that would run a servo. One of the fun things I learned from this process is that facial recognition software has a hard time recognizing people of color or people with facial hair. For example, I at the time had a rather large beard, would be recognized as different breeds of dogs.

Once the software was running and I had a base python script written, I began to make new iterations of disposable bots. I made four disposable bots: the scissor cobot, the tic tac cobot, the food container cobot, and the candy box cobot.

Once the software was running and I had a base python script written, I began to make new iterations of disposable bots. I made four disposable bots: the scissor cobot, the tic tac cobot, the food container cobot, and the candy box cobot.

I began exploring machine vision, which I could run and execute subscripts on a Raspberry Pi.

Once a face was recognized it would launch a separate python script that would run a servo.

I made four disposable bots: the scissor cobot, the tic tac cobot, the food container cobot, and the candy box cobot.

Once a face was recognized it would launch a separate python script that would run a servo.

I made four disposable bots: the scissor cobot, the tic tac cobot, the food container cobot, and the candy box cobot.

In congruence with writing and making, I began to illustrate, map, and define my point. I found that illustrating my ideas allowed for me to explore the bigger picture ideas I was trying to capture while writing allowed for me to speculate and play out those ideas in further details.(slide show to right) These two means of making then guided my physical making, and they also made it clear that the focus of this piece was not about disposable robots, but much more about division of labour and collaboration. Disposable robotics is still an interest of mine, but for the sake of this piece I pivoted and redefined my direction.

At this point, I was preparing the piece, which at the time had the working title Com - peer: A new kind of work experience, for the Media Design Practices work in progress show. This show helped me hone in what I was trying to further explore, and get more specific with the piece.

The piece was presented with the following preface:

“Moving away from a purely capitalistic mentality is necessary when implementing robotics into a work environment. Rather than displacing workers, workers should operate with and alongside robots. I have been exploring how we can design robots to augment, or work with, humans rather than replace them. What role does artificial intelligence play in this relationship, and how can we design this experience not just for humans, but for the algorithm as well.

As robotics becomes more affordable and attainable, many companies have, and will continue, investing in and implementing robots into their factories, displacing workers. Rather than replacing workers, we should design robots to work with humans, creating a new working dynamic. When robotics are introduced into carrying out a task they almost always experience some form of limitation where they make mistakes, these mishaps expose where humans need to be present in carrying out that task.

This increase in industrial use will result in even more reductions in price and improvement in technology, and robotics will eventually become so cheap that they will be implemented in every aspect of our daily life. As in industrial work environments, these relationships between human and robot will need to be defined.

I have chosen to explore how we can design robots that augment humans, through making robots that would be used in everyday aspects of our lives.

The bots you see here are made up of two categories, those that are actual robots, and perform their own unique functions when they recognize your face, and those that automate an action. These bots, in most cases, do not make the task easier, but very clearly begin to expose how the relationship between a robot and human worker will change. Additionally, they put into question whether the bot is augmenting the human or the device itself.”

At this point, I was preparing the piece, which at the time had the working title Com - peer: A new kind of work experience, for the Media Design Practices work in progress show. This show helped me hone in what I was trying to further explore, and get more specific with the piece.

The piece was presented with the following preface:

“Moving away from a purely capitalistic mentality is necessary when implementing robotics into a work environment. Rather than displacing workers, workers should operate with and alongside robots. I have been exploring how we can design robots to augment, or work with, humans rather than replace them. What role does artificial intelligence play in this relationship, and how can we design this experience not just for humans, but for the algorithm as well.

As robotics becomes more affordable and attainable, many companies have, and will continue, investing in and implementing robots into their factories, displacing workers. Rather than replacing workers, we should design robots to work with humans, creating a new working dynamic. When robotics are introduced into carrying out a task they almost always experience some form of limitation where they make mistakes, these mishaps expose where humans need to be present in carrying out that task.

This increase in industrial use will result in even more reductions in price and improvement in technology, and robotics will eventually become so cheap that they will be implemented in every aspect of our daily life. As in industrial work environments, these relationships between human and robot will need to be defined.

I have chosen to explore how we can design robots that augment humans, through making robots that would be used in everyday aspects of our lives.

The bots you see here are made up of two categories, those that are actual robots, and perform their own unique functions when they recognize your face, and those that automate an action. These bots, in most cases, do not make the task easier, but very clearly begin to expose how the relationship between a robot and human worker will change. Additionally, they put into question whether the bot is augmenting the human or the device itself.”

I began to illustrate, map, and define my point. I found that illustrating my ideas allowed for me to explore the bigger picture ideas I was trying to capture while writing allowed for me to speculate and play out those ideas in further details. (first slide show below)

At this point, I was preparing the piece, which at the time had the working title Com - peer: A new kind of work experience, for the Media Design Practices work in progress show.

At this point, I was preparing the piece, which at the time had the working title Com - peer: A new kind of work experience, for the Media Design Practices work in progress show.

At this stage of the piece, I was still very much focused on the labor side, which continued to be a theme, but it failed to get the user to really question what it would be like to work with a cobot. But a very important discovery was made from the devices from this show. It became very clear that all the devices, with the exception of the scissor bot, were failures at exploring collaboration between humans and intelligent devices. These devices were really forms of automation. Yes they used machine vision to engage the device, but they operated a single function when they recognized a users face, and that was it. This is important because they distinguished a level of interaction and user experience for both the scissor bot, the machine vision algorithm, and the user that worked with them. In the case of the scissor bot, the user had to collaborate with the algorithm and the device in order to cut paper, and in turn, the user didn't have to do as much work (making it more satisfying).

The piece was very well received and people really enjoyed the live interaction with the devices. The piece could have been installed a bit better, mainly wire management, but overall I thought it was a success. The show also allowed me to take a break from making and thinking about the piece which was a huge help. Having a bit of distance really allowed me to come back and focus on what the piece was really trying to explore.

The piece was very well received and people really enjoyed the live interaction with the devices. The piece could have been installed a bit better, mainly wire management, but overall I thought it was a success. The show also allowed me to take a break from making and thinking about the piece which was a huge help. Having a bit of distance really allowed me to come back and focus on what the piece was really trying to explore.

It became very clear that all the devices, with the exception of the scissor bot, were failures at exploring collaboration between humans and intelligent devices. These devices were really forms of automation. Yes they used machine vision to engage the device, but they operated a single function when they recognized a users face, and that was it. This is important because they distinguished a level of interaction and user experience for both the scissor bot, the machine vision algorithm, and the user that worked with them. In the case of the scissor bot, the user had to collaborate with the algorithm and the device in order to cut paper, and in turn, the user didn't have to do as much work (making it more satisfying).

Now that I knew I wanted to focus on how robotics and AI/ML could make tasks more satisfying, I decided to conduct a few guerilla interviews. I posted on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter asking people what their favorite household task was and to post a gif and a reason. Sadly no one responded from Twitter. People on Instagram only liked the post. Thankfully people on Facebook responded, and had quite a bit of fun with the GIF request. I documented all the GIF’s from each person as well as the conversations and follow up questions I had. These insights helped guide my new illustration work and helped focus my mind mapping. Additionally, based on the Facebook interviews, and the fact that laundry tends to be the benchmark for automation, I decided to purely focus on the laundry process for the project.

Around this time I also found Chindogu, the practice of almost useless inventions, which originated in Japan by Kenji Kawakami. I found, from the GIF’s, that when people are entertained and having fun, they are much more likely to open up about new ideas and talk about them, especially ones that seem far fetched or crazy. As with the GIF’s, Chindogu is very funny and odd, and became an influence in Simply Satisfaction. Harnessing that fun and weird influence allowed the pieces to be inviting and fun, while providing a platform to discuss the idea of making work/labor more satisfying for the worker, rather than purely focusing on efficiency or output.

Chindogu also helped frame another reference, Simone Giertz, that I had been following. Most people know her from her work making “Shitty Robots”. Her often surreal and funny approaches to making robots to solve certain problems really spoke out to me, but more importantly they harnessed a similar fun and weird nature that made having a very serious conversation about the role of robotics and AI in the future of labor less serious and something that users and viewers would be more willing to talk about and think about.

Around this time I also found Chindogu, the practice of almost useless inventions, which originated in Japan by Kenji Kawakami. I found, from the GIF’s, that when people are entertained and having fun, they are much more likely to open up about new ideas and talk about them, especially ones that seem far fetched or crazy. As with the GIF’s, Chindogu is very funny and odd, and became an influence in Simply Satisfaction. Harnessing that fun and weird influence allowed the pieces to be inviting and fun, while providing a platform to discuss the idea of making work/labor more satisfying for the worker, rather than purely focusing on efficiency or output.

Chindogu also helped frame another reference, Simone Giertz, that I had been following. Most people know her from her work making “Shitty Robots”. Her often surreal and funny approaches to making robots to solve certain problems really spoke out to me, but more importantly they harnessed a similar fun and weird nature that made having a very serious conversation about the role of robotics and AI in the future of labor less serious and something that users and viewers would be more willing to talk about and think about.

Now that I knew I wanted to focus on how robotics and AI/ML could make tasks more satisfying, I decided to conduct a few guerilla interviews asking people what their favorite household task was and to post a gif and a reason.

Based on the Facebook interviews, and the fact that laundry tends to be the benchmark for automation, I decided to purely focus on the laundry process for the project.

Based on the Facebook interviews, and the fact that laundry tends to be the benchmark for automation, I decided to purely focus on the laundry process for the project.

At this point I pivoted a bit from mapping and illustrating to role playing. I wanted to role play what it would be like to have a speculative device or devices that automated the whole laundry process and see what possible interactions and experiences that would occur or be needed for such a working relationship. By role playing I could explore this interaction without sinking a lot of time into building something that would not result in a successful and informative experiment. It also allowed me to explore the whole laundry process from beginning to end, which I hadn’t done before. I filmed this experiment from two perspectives to capture a point of view of each character, and wanted the human user, Gleb, to direct automation, me, around. By doing this I wanted to eliminate as much assumptions on my part as possible, while gaining as many insights from Gleb as possible. This sketch help call out for possible places of automation for cobots in the process, rather than looking at logistical or engineering limitations. Additionally role playing identified different forms of human communications/ interactions that would be beneficial for a cobot to understand. Outside of the very apparent voice commands in the experiment, which I wasn’t as interested in because there are many commercial devices that explore this experience, it was clear that hand gestures and the ability for the device to be able to recognize its human counterpart was necessary. This experiment was very successful for these reasons, however it was still a human interacting with another human, which fails to identify complications or unforeseen issues when interacting with a device. In a lot of ways it was my cardboard prototype for this piece.

I wanted to role play what it would be like to have a speculative device or devices that automated the whole laundry process and see what possible interactions and experiences that would occur or be needed for such a working relationship.

This sketch help call out for possible places of automation for cobots in the process.

Additionally role playing identified different forms of human communications/ interactions that would be beneficial for a cobot to understand. Outside of the very apparent voice commands in the experiment, it was clear that hand gestures and the ability for the device to be able to recognize its human counterpart was necessary.

In a lot of ways it was my cardboard prototype for this piece.

This sketch help call out for possible places of automation for cobots in the process.

Additionally role playing identified different forms of human communications/ interactions that would be beneficial for a cobot to understand. Outside of the very apparent voice commands in the experiment, it was clear that hand gestures and the ability for the device to be able to recognize its human counterpart was necessary.

In a lot of ways it was my cardboard prototype for this piece.

Now having some pain points identified, I began illustrating possible devices that would address these scenarios. In addition to illustrating I began animating some of the possible functionalities of the devices, which allowed me to explore and brainstorm much faster than building right away. At this point in the piece I was approaching the final show, and needed to work as smart as possible to ensure the time spent making was focused and constructive, allowing for the best possible insights to be revealed. It was also important that I eliminate any ideas that gamified the task in any way, the project was becoming more defined, and it was clear that it wasn’t about adding a device that made the task more fun. Similarly it became apparent that the devices shouldn’t make the process more convenient, because although convienence can make a task more enjoyable, convienence focuses on efficiency rather than satisfaction.

I went back to look through the Facebook interviews and realized that of those who said they found doing laundry satisfying all had different parts of the process that they enjoyed. Through critiques and some informal follow ups I found that not only did people enjoy one or two aspects of the laundry process, they also tended to dread the rest of it. This is when it became clear that this enjoyment of a task varies from person to person, but there is always one part that is distinctly pleasant. This part will change over time for each user, and requires a form of automation that is collaborative, allowing for the user to step in and out of any part of the process. It also repositions the user in new roles that traditionally would not exist, like assembling the automation, training the automation, and being trained by the automation.

With these insights and many ideas sketched out, I decided to make each device explore what different types of user experience with cobots could exist centered around key parts of the laundry process. I began making the devices based off the illustrations and animations. The scissor cobot explored what it would be like to have to collaborate with an algorithm and a cobot to cut fabric or strey threads. A later iteration had the option for the user to assemble and disassemble the cobot, which was another task people said they found satisfying.

I went back to look through the Facebook interviews and realized that of those who said they found doing laundry satisfying all had different parts of the process that they enjoyed. Through critiques and some informal follow ups I found that not only did people enjoy one or two aspects of the laundry process, they also tended to dread the rest of it. This is when it became clear that this enjoyment of a task varies from person to person, but there is always one part that is distinctly pleasant. This part will change over time for each user, and requires a form of automation that is collaborative, allowing for the user to step in and out of any part of the process. It also repositions the user in new roles that traditionally would not exist, like assembling the automation, training the automation, and being trained by the automation.

With these insights and many ideas sketched out, I decided to make each device explore what different types of user experience with cobots could exist centered around key parts of the laundry process. I began making the devices based off the illustrations and animations. The scissor cobot explored what it would be like to have to collaborate with an algorithm and a cobot to cut fabric or strey threads. A later iteration had the option for the user to assemble and disassemble the cobot, which was another task people said they found satisfying.

It was clear that it wasn’t about adding a device that made the task more fun (specifically gamifying the task).

The devices shouldn’t make the process more convenient, because although convienence can make a task more enjoyable, convienence focuses on efficiency rather than satisfaction.

I found that not only did people enjoy one or two aspects of the laundry process, they also tended to dread the rest of it. This is when it became clear that this enjoyment of a task varies from person to person, but there is always one part that is distinctly pleasant. This part will change over time for each user, and requires a form of automation that is collaborative, allowing for the user to step in and out of any part of the process. It also repositions the user in new roles that traditionally would not exist, like assembling the automation, training the automation, and being trained by the automation.

Each device explore what different types of user experience with cobots could exist centered around key parts of the laundry process. I began making the devices based off the illustrations and animations. The scissor cobot explored what it would be like to have to collaborate with an algorithm and a cobot to cut fabric or strey threads.

The devices shouldn’t make the process more convenient, because although convienence can make a task more enjoyable, convienence focuses on efficiency rather than satisfaction.

I found that not only did people enjoy one or two aspects of the laundry process, they also tended to dread the rest of it. This is when it became clear that this enjoyment of a task varies from person to person, but there is always one part that is distinctly pleasant. This part will change over time for each user, and requires a form of automation that is collaborative, allowing for the user to step in and out of any part of the process. It also repositions the user in new roles that traditionally would not exist, like assembling the automation, training the automation, and being trained by the automation.

Each device explore what different types of user experience with cobots could exist centered around key parts of the laundry process. I began making the devices based off the illustrations and animations. The scissor cobot explored what it would be like to have to collaborate with an algorithm and a cobot to cut fabric or strey threads.

Next I began building the soap dispensing cobot, which the user would train the cobot on how to scoop and pour soap into their landry machine. This way for the users that hated getting their hands soapy and having to wash off the soap, which takes forever, they could train the cobot once and then never have to do it again, making the process more satisfying. With the facial recognition working, I began by writing a python script that moved the servos in the proper directions and amounts for the arm to do the general process. With the robotic arm using four servos the Raspberry Pi’s GPIO pins couldn’t handle the power output, so I had to start using a servo hat. Then as the user I had to sit down and fine tune the servo values so it worked for my laundry machine set up. While working with the soap cobot I ran into some material limitations. The servos were generating so much heat during training that the PLA would start to melt. I would have to make sure the form did not skew to much and rush the robotic arm into the freezer to bring the temperature down as fast as possible.

While working on the training and building of the robotic arm, I began working on building the laundry folding cobot, for those who don’t mind doing laundry, but absolutely loathe folding clothes (me). With this cobot, unlike with the collaboration with the arm, it trained you on how you should place the garment on its platform so it could fold your clothes exactly how you like them folded. While building I ran into some issues with the amount of weight the servos could handle. Up until now I was able to prototype with micro servos for pretty much everything (had to use metal geared servos), but with the weight of a shirt or even a pair of pants, I had to switch to a much more powerful servo. I chose to switch to a 20kg servo, which for many of the other devices would have been way too big in size. The folder needed three servos, which required a decent amount more of power, which meant I had to add a capacitor to my Raspberry Pi’s servo hat. This device was one of the most successful and rewarding devices out of the collection. (see video above)

While working on the training and building of the robotic arm, I began working on building the laundry folding cobot, for those who don’t mind doing laundry, but absolutely loathe folding clothes (me). With this cobot, unlike with the collaboration with the arm, it trained you on how you should place the garment on its platform so it could fold your clothes exactly how you like them folded. While building I ran into some issues with the amount of weight the servos could handle. Up until now I was able to prototype with micro servos for pretty much everything (had to use metal geared servos), but with the weight of a shirt or even a pair of pants, I had to switch to a much more powerful servo. I chose to switch to a 20kg servo, which for many of the other devices would have been way too big in size. The folder needed three servos, which required a decent amount more of power, which meant I had to add a capacitor to my Raspberry Pi’s servo hat. This device was one of the most successful and rewarding devices out of the collection. (see video above)

The soap dispensing cobot, which the user would train the cobot once on how to scoop and pour soap into their landry machine, and then never have to do it again, making the process more satisfying.

The laundry folding cobot, for those who don’t mind doing laundry, but absolutely loathe folding clothes. It trained you on how you should place the garment on its platform so it could fold your clothes exactly how you like them folded. The folder needed three servos, which required a decent amount more of power (I had toswitch to a 20kg servo), which meant I had to add a capacitor to my Raspberry Pi’s servo hat.For this cobot

The laundry folding cobot, for those who don’t mind doing laundry, but absolutely loathe folding clothes. It trained you on how you should place the garment on its platform so it could fold your clothes exactly how you like them folded. The folder needed three servos, which required a decent amount more of power (I had toswitch to a 20kg servo), which meant I had to add a capacitor to my Raspberry Pi’s servo hat.For this cobot

The last two cobots were less functioning and more of speculative design objects. The first was the laundry roller which a user might use, not because it was helpful or very functional, but because it was quirky and enjoyable to use. (see video above) I’m not going to talk too much about the laundry roller cobot because it was fully Wizard of Oz’d, and not to many insights were gained. However it did help the piece overall both aesthetically and by defining the bigger ideas. The last cobot was the laundry de-sorter, which separates laundry by density making separating clothes more fun and making it easier to fold clothes. The original idea was to use a catapult that was spring loaded (see bellow), but using a spring, or making a spring, big enough was dangerous. After re-examining the functionality and decided that I could prototype an iteration of this cobot using an air compressor (which we had in the studio, but soon found out was broken) and rig it so the cobot would be a laundry hamper that would launch the clean clothes out the bottom (see below). Working along that line of thought I built an air cannon, like the ones they use at sporting events, as a replacement for the air compressor. Sadly the air cannon I made, which would fit in the hamper, could not create enough pressure to move clothing. Again I had to Wizard of Oz this scenario. Although these last two cobots were less successful as tools of discovering insights for what user experiences would be, and what would be needed for working with cobots, they did serve the important purpose speculating past the insights that the first three cobots exposed. This foresight is needed to push viewers of the piece to question more than what is current or obvious.

The last two cobots were less functioning and more of speculative design objects. The first was the laundry roller which a user might use, not because it was helpful or very functional, but because it was quirky and enjoyable to use.

The last cobot was the laundry de-sorter, which separates laundry by density making separating clothes more fun and making it easier to fold clothes.

Although these last two cobots were less successful as tools of discovering insights they did serve the important purpose speculating past the insights that the first three cobots exposed. This foresight is needed to push viewers of the piece to question more than what is current or obvious.

The last cobot was the laundry de-sorter, which separates laundry by density making separating clothes more fun and making it easier to fold clothes.

Although these last two cobots were less successful as tools of discovering insights they did serve the important purpose speculating past the insights that the first three cobots exposed. This foresight is needed to push viewers of the piece to question more than what is current or obvious.

Overall this piece was extremely successful, and I learned a lot from it. I think it took a big step forward in exploring what user experience for artificial intelligence and collaborative robots is. In the future of AI, allowing users to be able to custom train their algorithm to best work collaboratively will develop better human centered user experience, but at the same time will start to build the foundation of how we create a better experience for the algorithm itself.

Similarly if the algorithm is training you, it needs to be designed in a way that it has the best ability to analyze your preferences without bias or assumptions. I think this is a big issue with the future of artificial intelligence, and it can be a double edged sword, as this technology evolves, we need to start being concerned, not so much on we push the boundaries of AI, but really start to think about how it is designed. What are the ethical implications of training and building an algorithm. I think user experience design for AI is an important factor in this innovation processes. User experience for AI will not be a one to one replica of what it is for human centered design, it can’t be. It might be more similar from a qualitative standpoint, and it will definitely be different from a quantitative standpoint, but it’s very much needed. Through this piece I believe user experience for AI is reflexive to human centered user experience. In order for it to be designed and developed, it has to be built keeping in mind the needs and interactions of the users it will be collaborating with. Ultimately the algorithm will be working with humans at its output.

I don’t think there were any major failures in the piece, but there are definitely things that if there were more time (I know this is always the case) that I would have like to develop more. In particular, both the Laundry Rolling cobot and the Laundry De-Sorter cobot, I wish had more time to implement machine vision and actually build out the mechanics of the devices. Another big thing I think in new iterations of the cobots that I would like to explore is how the user experience changes when interacting both with machine vision and voice user interfaces. Personal privacy is a big user issue for people using smart home devices, and was also a big design challenge for Google Clips, and I believe that using a combination of both machine learning applications could fix that pain point.

Similarly if the algorithm is training you, it needs to be designed in a way that it has the best ability to analyze your preferences without bias or assumptions. I think this is a big issue with the future of artificial intelligence, and it can be a double edged sword, as this technology evolves, we need to start being concerned, not so much on we push the boundaries of AI, but really start to think about how it is designed. What are the ethical implications of training and building an algorithm. I think user experience design for AI is an important factor in this innovation processes. User experience for AI will not be a one to one replica of what it is for human centered design, it can’t be. It might be more similar from a qualitative standpoint, and it will definitely be different from a quantitative standpoint, but it’s very much needed. Through this piece I believe user experience for AI is reflexive to human centered user experience. In order for it to be designed and developed, it has to be built keeping in mind the needs and interactions of the users it will be collaborating with. Ultimately the algorithm will be working with humans at its output.

I don’t think there were any major failures in the piece, but there are definitely things that if there were more time (I know this is always the case) that I would have like to develop more. In particular, both the Laundry Rolling cobot and the Laundry De-Sorter cobot, I wish had more time to implement machine vision and actually build out the mechanics of the devices. Another big thing I think in new iterations of the cobots that I would like to explore is how the user experience changes when interacting both with machine vision and voice user interfaces. Personal privacy is a big user issue for people using smart home devices, and was also a big design challenge for Google Clips, and I believe that using a combination of both machine learning applications could fix that pain point.

Overall this piece was extremely successful, and I learned a lot from it. I think it took a big step forward in exploring what user experience for artificial intelligence and collaborative robots is. In the future of AI, allowing users to be able to custom train their algorithm to best work collaboratively will develop better human centered user experience, but at the same time will start to build the foundation of how we create a better experience for the algorithm itself.

As this technology evolves, we need to start being concerned, not so much on we push the boundaries of AI, but really start to think about how it is designed. What are the ethical implications of training and building an algorithm. I think user experience design for AI is an important factor in this innovation processes. User experience for AI will not be a one to one replica of what it is for human centered design, it can’t be. It might be more similar from a qualitative standpoint, and it will definitely be different from a quantitative standpoint, but it’s very much needed. Through this piece I believe user experience for AI is reflexive to human centered user experience. In order for it to be designed and developed, it has to be built keeping in mind the needs and interactions of the users it will be collaborating with. Ultimately the algorithm will be working with humans at its output.

I think in new iterations of the cobots that I would like to explore is how the user experience changes when interacting both with machine vision and voice user interfaces.

As this technology evolves, we need to start being concerned, not so much on we push the boundaries of AI, but really start to think about how it is designed. What are the ethical implications of training and building an algorithm. I think user experience design for AI is an important factor in this innovation processes. User experience for AI will not be a one to one replica of what it is for human centered design, it can’t be. It might be more similar from a qualitative standpoint, and it will definitely be different from a quantitative standpoint, but it’s very much needed. Through this piece I believe user experience for AI is reflexive to human centered user experience. In order for it to be designed and developed, it has to be built keeping in mind the needs and interactions of the users it will be collaborating with. Ultimately the algorithm will be working with humans at its output.

I think in new iterations of the cobots that I would like to explore is how the user experience changes when interacting both with machine vision and voice user interfaces.

All works © Michael Milano 2010-2019. Please do not reproduce without the expressed written consent of Michael Milano.