All media are extensions of some human faculty – psychic or physical

Four week graduate school project.

Specification: Illustration, animation, speculative design

Execution: Illustrator, After Effects

Piece: Intermediary Transcendence Proxy is an animated piece exploring the future of labor.

Specification: Illustration, animation, speculative design

Execution: Illustrator, After Effects

Piece: Intermediary Transcendence Proxy is an animated piece exploring the future of labor.

Intermediary Transcendence Proxy exploration of the future of labor that challenges and pushes the limits of Marshall Mcluhan's concepts of media. Specifically the quote:

All media are extensions of some human faculty – psychic or physical

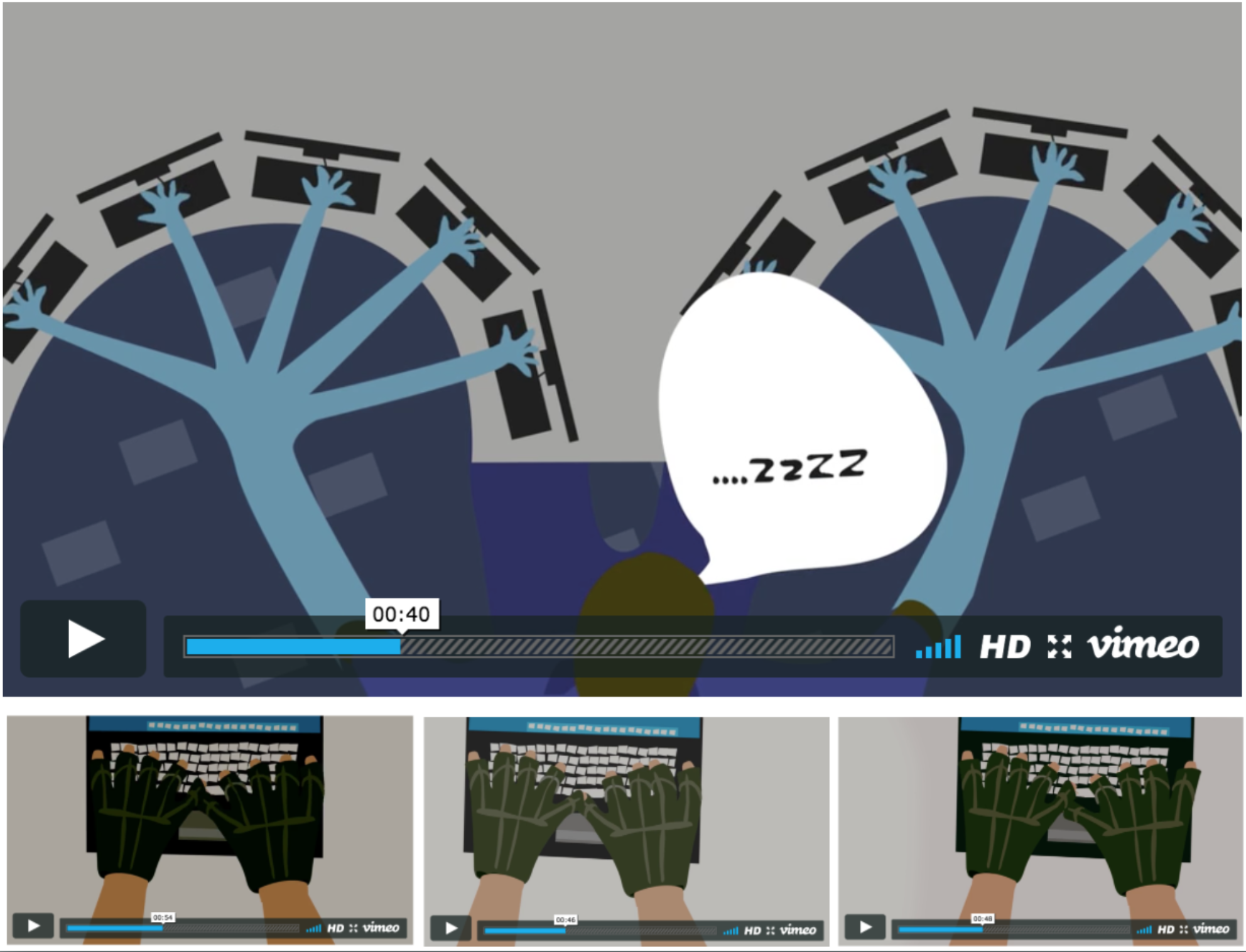

Each scenario explores a technical device’s functionality while putting the power and labor back in the hands of the worker. In the first scenario, the office worker is simply a vessel for a community of outsource workers around the world. The office “worker” falls asleep as contract workers type away getting many jobs done at the same time.

The second scenario explores how labor would change if we had actual workers smelling for hazardous material rather than relying on sensors and machines. Airport workers would walk around with smell wands that detect security threats, while, from a safe distance, workers would wear smelling apparatuses that would allow them to sniff out dangers.

_Process

This project started with my curiosity of how cyber security jobs will evolve in the future. Cyber attacks will continue to occur and will likely be more frequent. This, in combination, with the fact that most attacks are not complex in nature, would make the tasks that need to be carried out much simpler, and something that the average factory worker would be capable of completing.

Envisioning the work environments and devices of future factory cyber security worker allowed me to evolve my focus to start to explore how hackers would could exploit the internet of things. Specifically I began to explore how hackers could exploit medical devices. In the future (and to some degree currently) medical devices connect to the internet making them vulnerable. Incidents like this wouldn't be far off considering the situation in Glendale, CA on February 18th, 2016, where hackers held a hospital for ransom, and the hospital eventually paid 40 bitcoin.

https://sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com/2016/02/18/california-hospital-ransomware-attack-hackers/

All media are extensions of some human faculty – psychic or physical

Each scenario explores a technical device’s functionality while putting the power and labor back in the hands of the worker. In the first scenario, the office worker is simply a vessel for a community of outsource workers around the world. The office “worker” falls asleep as contract workers type away getting many jobs done at the same time.

The second scenario explores how labor would change if we had actual workers smelling for hazardous material rather than relying on sensors and machines. Airport workers would walk around with smell wands that detect security threats, while, from a safe distance, workers would wear smelling apparatuses that would allow them to sniff out dangers.

_Process

This project started with my curiosity of how cyber security jobs will evolve in the future. Cyber attacks will continue to occur and will likely be more frequent. This, in combination, with the fact that most attacks are not complex in nature, would make the tasks that need to be carried out much simpler, and something that the average factory worker would be capable of completing.

Envisioning the work environments and devices of future factory cyber security worker allowed me to evolve my focus to start to explore how hackers would could exploit the internet of things. Specifically I began to explore how hackers could exploit medical devices. In the future (and to some degree currently) medical devices connect to the internet making them vulnerable. Incidents like this wouldn't be far off considering the situation in Glendale, CA on February 18th, 2016, where hackers held a hospital for ransom, and the hospital eventually paid 40 bitcoin.

https://sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com/2016/02/18/california-hospital-ransomware-attack-hackers/

Then I started to question how hacking medical devices, in a more white or grey hat positionality, could be used for good. What if an underground network formed helping the poor get access to devices that relieved people with phantom limb syndrome of the pain they experienced.

Ultimately I felt that focus on medical devices and how they could be hacked/ exploited was to literal and did not address the future of work. But it did start to form a question about how devices of labour would change in a possible future. This is where I began to form the more surreal interpretation of Marshall Mcluhan’s concepts of media.

Ultimately I felt that focus on medical devices and how they could be hacked/ exploited was to literal and did not address the future of work. But it did start to form a question about how devices of labour would change in a possible future. This is where I began to form the more surreal interpretation of Marshall Mcluhan’s concepts of media.

_Critical Reflection

This is definitely a project I would like to continue to explore. As much as I would like to continue animating new scenarios, I think it would be more productive, and much more powerful to explore options that are more tangible. I’m not sure what media that should be, but it would be interesting to physically make them, or at the very least turn them into an interactive onscreen game of some kind.(This project later evolved into my thesis project Simply Satisfaction: Cobots do everything (but what you want to do))

// Tools

Illustrator

After Effects

Illustrator

After Effects

// Critical Analysis: Intermediary Transcendence Proxy

Intermediary Transcendence Proxy (ITP), 11.16.16, is an exploration of labor in a future where proxies are used in jobs that currently would be done by an automated machine. In this narrative proxies are defined by a technological tool that serves as an intermediary to the task at hand. These proxies explore a technical device’s functionality while putting the power and labor back in the hands of the worker. Each of the three scenarios challenge and push the limits of Marshall McLuhan's concepts of media. Specifically the idea that, “All media are extensions of some human faculty – psychic or physical” (The Medium is the Massage, McLuhan 26). This is explored by focusing on an absurd outcome of each proxy.

In the first scenario, the office worker is simply a vessel for a community of outsourced workers around the world. The office “worker” sits at his desk puts on the office issued arm proxies (pictured below) and starts his work day. At the same time people from all over the world put on their work gloves and begin working remotely to operate his arm proxies (see below). He falls asleep as the contract workers type away getting many jobs done at the same time.

The second scenario explores how labor would change if airports hired human workers to smell for and detect hazardous material rather than relying on sensors and machines. Airport workers walk around with smell wands that detect security threats, while, from a safe distance, outsourced workers use smelling apparatuses that allow them to sniff out dangers. As in the first scenario, the second scenario explores the human error in the situation. This happens when the TSA agent begins to get distracted and use the wand to smell gum on the ground.

The third scenario explores labor in a port. As a dock worker starts to use her box unloader, the viewer is exposed to how it functions. Rows and rows of workers individually operate each of the proxy’s arms and legs. The dock worker remains sedentary while all the remote workers control everything. Here too, human error is exposed, when the proxy drops boxes and the worker does nothing about it.

There are several common threads throughout ITP that explore the relationship between machines and humans in the workplace. One of the questions explored by ITP is whether machines are inherently better at some jobs than people are, and once a job is mechanized, whether it can be reclaimed by the human workforce. In ITP, high-tech proxies are implemented to over-simplify jobs normally done by machines so the average person can perform them, and the piece emphasizes the human error that becomes present by bringing the job back to the human hand. Following this point it is brought into question whether the device is the proxy, or is the human “operating” it. This is put into question because there is very little distinguishing who/what is controlling who. Is the worker operating the device, or is the device in fact only functioning because it is being occupied by the worker, making the worker the proxy. Or is the worker’s only role to supervise the proxy? Lastly, ITP questions whether mechanization is always more efficient. This future society has created jobs that don’t really need to exist because the mechanization has actually complicated the workflow without bringing any improvements. These three aspects of the three scenarios fall within both speculative design and adversarial design. In addition to these themes, there are aspects of ITP that lend themselves more to one than the other, and in some ways ITP falls short of being completely one or the other.

Adversarial design was introduced by Carl Disalvo in his book “Adversarial Design”.

Adversarial design as an intentional practice of inquiry into the political condition moves political design beyond awareness raising and critique… Design can produce a shift toward action that models alternative presents and possible futures in material and experiential form… Projects such as the CCD-Me Not Umbrella (2009b) and the Ad-hoc Dark (roast) Network Travel Mug (2009a) do more than raise awareness and critique. They instantiate a possibility for another ordering of sociotechnical structures that allows us to act in the world a different way. (Disalvo, pg 118-19)

http://survival.sentientcity.net/

Adversarial design are “works that express or enable... agonism.” (Disalvo, pg 2)

Agonism: is a political theory that emphasizes the potentially positive aspects of certain (but not all) forms of political conflict, namely, in the ability to enforce or reenforce democratic inclusion. This view accepts a permanent place for such conflict, while seeking to show how we might accept and channel this positively.

(Fiala, pg 161)

ITP has many characteristics of adversarial design, specifically its focus on creating agonism. The piece puts the viewer in a political conflict that makes them question whether in the future we will have the need to create jobs for the sake of having jobs or will automation still remain, and how would the factor of human error play into this scenario. This political conflict is not defined by specific political parties, but by the frameworks of socio-economic and labor issues. This topic is further challenged by questioning what the continued use of outsourcing will do, and to what ends does it factor into the larger labor market. It is explored beyond this by pointing out that the future of work may not be local, but instead it will be a global network of workers collaborating in real time using high tech proxy devices.

This political conflict is furthered by exploring future labor, while it expresses the opinion that even with new high-tech equipment focused on making things more efficient, human error will impede it. It also points out that existence of outsource and automatization will continue, but it brings into question where will the average worker be placed. And who is the primary worker? Is it the person acting as a proxy? Or is it the multiple workers working from a factory/office?

For us, the purpose of speculation is to “unsettle the present rather than predict the future.”17 But to fully exploit this potential, design needs to decouple itself from industry, develop its social imagination more fully, embrace speculative culture, and then, maybe, as MoMA curator Paola Antonelli suggests, we might see the beginnings of a theoretical form of design dedicated to thinking, reflecting, inspiring, and providing new perspectives on some of the challenges facing us. (Dunne & Raby, pg 88)

ITP also roots itself in speculative design because it extends just past an aspect of work that in many ways are already happening, and asks the viewer to relate to something that is slightly plausible, but clearly absurd. This invites the viewer to consider the specific alternate future, and is further achieved by getting the viewer to believe in the quasi-realistic depiction of this future. This future gets the viewer to start thinking about many questions about the nature of work, starting with how automatization and technology fit into it. And, similarly to its agonistic themes, it raises the question of what is the role of the everyday worker in labor is in this future. It is similar to the Black Mirror episode (see below (a)) referenced in Speculative Everything as an example of speculative design, in that it reframes what labor might be in the future. In the Black Mirror episode “workers” have to use a stationary cycle to earn income. It’s an absurd notion to be paid to cycle, but it makes the viewer question what future labor might be, and who will be doing it. Dunne & Raby’s Overpopulated Planet also brings into question a specific future of labor, where apparatuses are used to extract nutrients from non-food items to combat the need for food in an overpopulated world. Other than the obvious use of a proxy like object, Overpopulated Planet (see below (b)) has a similar absurdity to it, which invites the viewer to question the role that possible future technology will play in the a world that has a shift in what labor is. In this specific future, are jobs created just for the sake of keeping people working, or is there a specific reason for these proxies, that allows the job to be done? Is this a more efficient way of getting work done? The viewer is left with the question of who is the actual proxy?The piece also proposes the question of who is the actual proxy? This is put into question because it isn’t clear whether the apparatus needs the person in order for it to function or if the person needs the apparatus to carry out the task. This further puts into question the hierarchy of future labor. In many ways the worker becomes the proxy, and the outsourced workers are the primary conductors of labor, which in many ways flips the current norm upside down.

Adversarial design are “works that express or enable... agonism.” (Disalvo, pg 2)

Agonism: is a political theory that emphasizes the potentially positive aspects of certain (but not all) forms of political conflict, namely, in the ability to enforce or reenforce democratic inclusion. This view accepts a permanent place for such conflict, while seeking to show how we might accept and channel this positively.

(Fiala, pg 161)

ITP has many characteristics of adversarial design, specifically its focus on creating agonism. The piece puts the viewer in a political conflict that makes them question whether in the future we will have the need to create jobs for the sake of having jobs or will automation still remain, and how would the factor of human error play into this scenario. This political conflict is not defined by specific political parties, but by the frameworks of socio-economic and labor issues. This topic is further challenged by questioning what the continued use of outsourcing will do, and to what ends does it factor into the larger labor market. It is explored beyond this by pointing out that the future of work may not be local, but instead it will be a global network of workers collaborating in real time using high tech proxy devices.

This political conflict is furthered by exploring future labor, while it expresses the opinion that even with new high-tech equipment focused on making things more efficient, human error will impede it. It also points out that existence of outsource and automatization will continue, but it brings into question where will the average worker be placed. And who is the primary worker? Is it the person acting as a proxy? Or is it the multiple workers working from a factory/office?

For us, the purpose of speculation is to “unsettle the present rather than predict the future.”17 But to fully exploit this potential, design needs to decouple itself from industry, develop its social imagination more fully, embrace speculative culture, and then, maybe, as MoMA curator Paola Antonelli suggests, we might see the beginnings of a theoretical form of design dedicated to thinking, reflecting, inspiring, and providing new perspectives on some of the challenges facing us. (Dunne & Raby, pg 88)

ITP also roots itself in speculative design because it extends just past an aspect of work that in many ways are already happening, and asks the viewer to relate to something that is slightly plausible, but clearly absurd. This invites the viewer to consider the specific alternate future, and is further achieved by getting the viewer to believe in the quasi-realistic depiction of this future. This future gets the viewer to start thinking about many questions about the nature of work, starting with how automatization and technology fit into it. And, similarly to its agonistic themes, it raises the question of what is the role of the everyday worker in labor is in this future. It is similar to the Black Mirror episode (see below (a)) referenced in Speculative Everything as an example of speculative design, in that it reframes what labor might be in the future. In the Black Mirror episode “workers” have to use a stationary cycle to earn income. It’s an absurd notion to be paid to cycle, but it makes the viewer question what future labor might be, and who will be doing it. Dunne & Raby’s Overpopulated Planet also brings into question a specific future of labor, where apparatuses are used to extract nutrients from non-food items to combat the need for food in an overpopulated world. Other than the obvious use of a proxy like object, Overpopulated Planet (see below (b)) has a similar absurdity to it, which invites the viewer to question the role that possible future technology will play in the a world that has a shift in what labor is. In this specific future, are jobs created just for the sake of keeping people working, or is there a specific reason for these proxies, that allows the job to be done? Is this a more efficient way of getting work done? The viewer is left with the question of who is the actual proxy?The piece also proposes the question of who is the actual proxy? This is put into question because it isn’t clear whether the apparatus needs the person in order for it to function or if the person needs the apparatus to carry out the task. This further puts into question the hierarchy of future labor. In many ways the worker becomes the proxy, and the outsourced workers are the primary conductors of labor, which in many ways flips the current norm upside down.

(Charlie Brooker, Black Mirror, 2012)

(Dunne & Raby, Designs for an Overpopulated Planet, No. 1: Foragers, 2009)

As much as ITP lends itself to adversarial design, specifically agonism, there are many ways in which it does not. From the start of the project my focus was never on situating this project from a point of agonism. By nature it has an opinion/ stance and situates the viewer in a political conflict, but even though it focuses on several conflicting factors/opinions it doesn’t really put the viewer in the constant tension that adversarial design dictates. If I were to do another iteration of ITP I would take a more of an adversarial design point of view, which would require me to do a few things differently. I would have to figure out a way to further situate the viewer in a position of having to form an opinion or align with one side or the other, fulfilling the need of political conflict. I would need to more clearly depict what those factors would be. In addition, I feel like there's a certain level of interaction that is missing from ITP to truly be considered adversarial design. The viewer, is just that, a witness to a narrative. In no way do they get a greater understanding of the dynamics of the topics of future labor being portrayed.

This piece is more speculative design then it is adversarial design. From the start ITP always been about proposing a specific future, and it depicts that future to the viewers in a less than believable manner. By presenting this depiction, I wanted the viewers to think about the possibility of this future’s absurdity, and to then start to realize that in many ways it’s totally possible, and beginning to happen. The absurdity of this piece, doesn’t completely exclude the possibility of it becoming adversarial design, but its function in creating a political conflict doesn’t quite exist and needs to be better framed. Most of the more absurd examples Disalvo references (like Omo, see below), are odd/surreal, but that that oddity is a tool to reinforce an interaction between the user and the design that situates the user in agonism. This further allows them, through interaction of some kind, to develop a greater understanding and to form their own opinion on the subject matter. I think in future iterations of this piece it would be interesting to make something tangible, whether that be a piece of software or physical space that allows for the user to further experience this series of dynamics. Actually making the interactive proxies, with corresponding software, to immerse the user into this proposed future would be an interesting next step, and would provide the platform needed to further discuss the issues at hand and create a stronger sense of agonism.

(Dunne & Raby, Designs for an Overpopulated Planet, No. 1: Foragers, 2009)

As much as ITP lends itself to adversarial design, specifically agonism, there are many ways in which it does not. From the start of the project my focus was never on situating this project from a point of agonism. By nature it has an opinion/ stance and situates the viewer in a political conflict, but even though it focuses on several conflicting factors/opinions it doesn’t really put the viewer in the constant tension that adversarial design dictates. If I were to do another iteration of ITP I would take a more of an adversarial design point of view, which would require me to do a few things differently. I would have to figure out a way to further situate the viewer in a position of having to form an opinion or align with one side or the other, fulfilling the need of political conflict. I would need to more clearly depict what those factors would be. In addition, I feel like there's a certain level of interaction that is missing from ITP to truly be considered adversarial design. The viewer, is just that, a witness to a narrative. In no way do they get a greater understanding of the dynamics of the topics of future labor being portrayed.

This piece is more speculative design then it is adversarial design. From the start ITP always been about proposing a specific future, and it depicts that future to the viewers in a less than believable manner. By presenting this depiction, I wanted the viewers to think about the possibility of this future’s absurdity, and to then start to realize that in many ways it’s totally possible, and beginning to happen. The absurdity of this piece, doesn’t completely exclude the possibility of it becoming adversarial design, but its function in creating a political conflict doesn’t quite exist and needs to be better framed. Most of the more absurd examples Disalvo references (like Omo, see below), are odd/surreal, but that that oddity is a tool to reinforce an interaction between the user and the design that situates the user in agonism. This further allows them, through interaction of some kind, to develop a greater understanding and to form their own opinion on the subject matter. I think in future iterations of this piece it would be interesting to make something tangible, whether that be a piece of software or physical space that allows for the user to further experience this series of dynamics. Actually making the interactive proxies, with corresponding software, to immerse the user into this proposed future would be an interesting next step, and would provide the platform needed to further discuss the issues at hand and create a stronger sense of agonism.

(Kelly Dobson, Omo (2007b)

(Kelly Dobson, Omo (2007b)

Shepard, Mark. "Sentient City Survival Kit." Sentient City Survival Kit. Accessed February 20, 2017. http://survival.sentientcity.net/.

Brooker, Charlie, and Kanak Huq, writers. "Fifteen Million Merits." In Black Mirror. December 11, 2011.

Disalvo, Carl. Adversarial design. Place of publication not identified: Mit Press, 2015.

Dunne, Anthony, and Fiona Raby. Speculative everything: design, fiction, and social dreaming. S.l.: MIT, 2014.

Fiala, Andrew. The Bloomsbury companion to political philosophy. London: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2017.

All works © Michael Milano 2010-2019. Please do not reproduce without the expressed written consent of Michael Milano.